The white Aylesbury is, and deservedly, a universal favourite. Its snowy plumage and comfortable comportment make it a credit to the poultry yard, while its broad and deep breast and its ample back, convey the assurance that its satisfaction will not cease at its death.

In parts of Buckinghamshire, England, this member of the duck family were bred on an extensive scale; not on plains and commons, however, as might be naturally imagined, but in the abodes of the cottagers…

…Round the walls of the living rooms, and of the bedroom even, are fixed rows of wooden boxes, lined with hay; and it is the business of the wife and children to nurse and comfort the feathered lodgers, to feed the little ducklings and to take the old ones out for an airing. Sometimes the ‘stock ducks’ are the cottagers own property, but it more frequently happens that they are entrusted to his care by a wholesale breeder, who pays him so much per score for all ducklings properly raised. To be perfect, the Aylesbury duck should be plump, pure white, with yellow feet and a flesh coloured beak.

Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, 1861

The Aylesbury is still probably the best known breed of domestic duck. It’s origins can be traced back to the wild mallard. By the start of the 18th century, selective breeding of the common duck – probably a coloured domesticated type of mallard,- produced a white duck which was known as ‘English white’. These ducks are referred to by the Rev St John Priest writing in 1810: “Ducks form a material article at market from Aylesbury and places adjacent; they are white and as it seems of an early breed.”

The stock ducks were usually kept in the outlying villages and hatching eggs supplied to the town-dwelling cottagers. Broody hens were used and the first eggs laid in November would be ready for market in February after the close of the game season. The ducklings fattened quickly to about 4 lbs at 8 weeks when it was important to kill them before the first moult or the birds would be stubby. The white plumage was encouraged as pure white feathers and down attracted higher prices from the East London dealers for pillow and quilt filling.

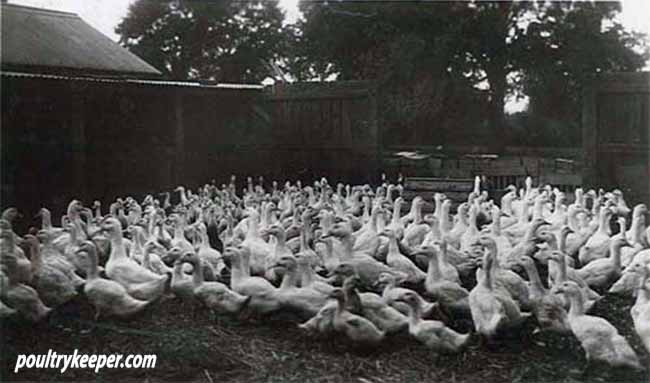

A flock of young Aylesbury ducks kept in Aylesbury towards the end of the 18th Century.

The industry in Aylesbury continued to expand into the nearby villages and it is recorded that over one ton of ducks were regularly taken by train from Aylesbury at night for the London markets. The introduction of the Pekin duck from China in 1873 and subsequent cross breeding with the Aylesbury produced a very hardy bird with early maturity but a creamy plumage and yellow bill. This cross was so successful that it became increasingly difficult to obtain pure Aylesbury stock. With the introduction of incubators and artificial rearing methods, the production of ducks in Aylesbury declined from 1910 onwards. The Aylesbury x Pekin cross is still the basis for the table duck market today, now established in Lincolnshire and Norfolk.

With the introduction of village poultry shows in the early 19th century, a standard for the breed began to be created. The First National Poultry Show was held in the Zoological Gardens in London in June, 1845. Poultry breeding began to establish its importance in agriculture. In 1853, the Royal Agricultural Society of England and the Bath and West of England Society included a poultry section in their shows for the first time.

In 1890, Mrs Seamons, a leading exhibitor of Aylesbury ducks, wrote that “the weight of the drake was good at 9 lbs and the duck at 8 lbs, but these are exceptional. The heaviest pen that I ever had was a trio at 32 lbs when they left home and when judged at Birmingham, where they won the cup, they weighed 30 lbs”. Birmingham Show was unusual in the fact that weight was more important than standards.

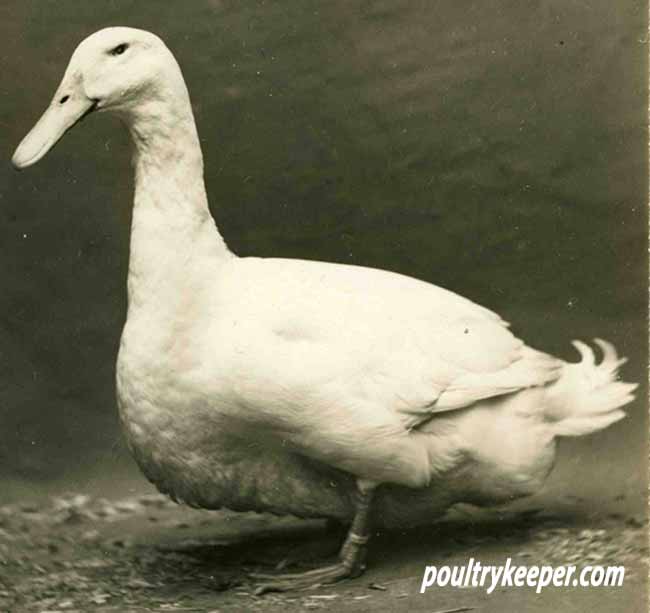

An Aylesbury Drake from – Photograph Copyright ‘The Rice Collection’. Taken Circa 1920-40.

The exhibition Aylesbury has always presented a problem in maintaining the white feather and bill colour – “as pink as a lady’s nail” (Book of Poultry, Lewis Wright, 1891). Traditionally, this was achieved by allowing the ducks limited access to sunlight and the use of gravel – readily available in the Vale of Aylesbury – in the water troughs.

Weights of 10 lbs for drakes and 9 lbs for ducks are standard for the breed today and birds are also judged on type, size, conformation and condition. The Aylesbury is a hardy, adaptable breed but is most suited to level, well-drained ground. Appleyard [Reginald Appleyard was a well-known writer and breeder of domestic waterfowl of the 1920’s and 1930’s – Ed.] quotes advice given to him of “never go on struggling to keep and breed birds which do not suit your district and climate.” Aylesbury ducks seem to have adapted to most conditions and have flourished worldwide.

A mating of 1 drake to 2 or 3 ducks is best for the large exhibition type birds but 1 drake with 5 or 6 females may be used with the lighter utility types. To be successful with ducks it is essential to have them tame, happy and contented both with you and with their surroundings. Always warn them of your approach and you will be rewarded with long, drawn out quacks of greeting. The ducks will proceed to tell you at length all that has happened to them that day, or so it seems. Aylesburys, being heavy birds, quickly go off their legs and flounder on their keels or heap on top of each other if panicked. Generally they are placid and good-tempered.

The female may lay over 100 eggs in a season. As most ducks lay before 9am, the eggs can be collected when releasing the birds in the morning. It becomes a case of hide-and-seek with free-range birds and they will frequently change their scrape or nest. It is helpful to leave a white stone or dummy egg in the nest. The eggs are white or greenish white and large (3oz). The yolk is round and orange and the white sets more firmly than a chicken egg and makes excellent meringues.

Aylesburys are not generally good sitters, hence the advice from Rebeccah Puddle-Duck to her sister Jemima: “I have not the patience to sit on a nest for 28 days. No more have you, Jemima. You would let them go cold, you know you would ! Jemima tried to hide her eggs but they were always found and carried off.” (The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck by Beatrix Potter)

Aylesbury Ducks owned by John Richards. Photo courtesy of the BWA.

Owing to their large keel and body weight, Aylesburys tend to be a little clumsy as broodies and mothers. They are also too heavy to become airborne in contradiction to Beatrix Potter who wrote that “Jemima Puddle-Duck ran downhill a few yards flapping her shawl and then she jumped off into the air. She flew beautifully when she had got a good start.”

They do not require high fencing although protection from predators is important. Aylesburys tend to suffer from cramp and rheumatism and need a dry, draught-free hut but at the same time it is important to have good ventilation. They have been known to live for up to 10 years and to lay for 6 years.

Properly cared for and fed with sensible foods, Aylesbury ducks will respond to their keeper and give great pleasure.

[note style=”info” show_icon=”true”]There are more photos and breed information on our breed page for the Aylesbury duck here.[/note]