The lavender variety of poultry is very beautiful. The effect is born from the lavender gene being present in a black fowl and reducing the quantity of pigment allowed to express on each feather; instead of black, the feathers appear a much softer shade of pastel blue.

This shouldn’t be confused with the blue gene, however, as lavender fowl breed true so confusing or crossing the two varieties is not a good idea.

A pair of UK Lavender Pekins on a windy day

A pair of UK Lavender Pekins on a windy day

Being a recessive gene, lavender has to be present in pure form (2 doses) in a fowl to be visually observable. Black birds can carry the lavender gene without showing any traces of it.

And, many breeders outcross to black varieties of their chosen breed in order to improve their lavenders. They know that the black offspring must be lavender-carriers, so they can either breed back to the lavender parent and get 50% of each, or carry out a sibling mating where they will only get 25% lavenders (not personally recommended).

Keeping records

Crossing lavender to blacks may work well for lavender, but it is unlikely to improve the blacks. If you do have to make this cross, keep strict records so that anyone who buys stock from you knows what they are getting.

You know that the first cross offspring are all carriers of lavender. You also know that any subsequent black offspring (from a lavender-carrying black bred to lavender), will be carrying the lavender gene. The only time all this gets muddied is when you make a sibling mating from the first cross black birds (originating from your lavender to black)…

The black birds in generation 2 (which will emerge in 75% of the offspring), will give no clue as to whether they carry lavender – you will have no idea. This certainly won’t help your project, as you can’t gauge their usefulness, and you don’t really want to sell people lavender-carrying blacks; blacks should be true-breeding blacks!

Tail shredder

For some reason, the lavender gene has an unexplained linkage to an effect that makes the tail ‘ragged’ in some specimens. This has been nicknamed the ‘tail shredder’ gene by some breeders, probably because it looks like the affected birds have been dragged through a hedge.

Early stages of Lavender Wyandottes showing some specimens with the tail shredder gene. Created by Allan Brooker – Lavender is now standardised (Jan. 2014) by the Poultry Club of G.B.

I have seen some ‘otherwise-beautiful’ birds that have had the unfortunate ‘tail shredder’ problem. The good news is that the link can be broken and it is possible to produce lavenders with normal-feathered tails. In the UK, we have some fantastic Pekins and Araucanas that, through selection, have got past this issue.

UK Lavender Araucanas

Lavender in other varieties

Of course, lavender isn’t consigned to the self-colored varieties. It can be bred into any color form or pattern of fowl imaginable. However, unlike the blue gene, it doesn’t just affect the residual black pigment, but also has a huge impact on any red pigment which it turns to ‘straw.’

This is the main reason why it’s impossible to have red and lavender expressing in the same fowl. If it were possible, the blue gene would probably become redundant to a large degree: the breeders of Blue-Partridge over here would dearly love them to breed true without all the waste, but sadly they don’t, and lavender isn’t the answer.

It has become the answer, however, for varieties like true-breeding Blue-Silver and Coronation Wyandottes (like Columbian but with lavender replacing the black). These breed true and without any problems.

A Lavendar Orpington from Pricilla Middleton’s line.

A Lavendar Orpington from Pricilla Middleton’s line.

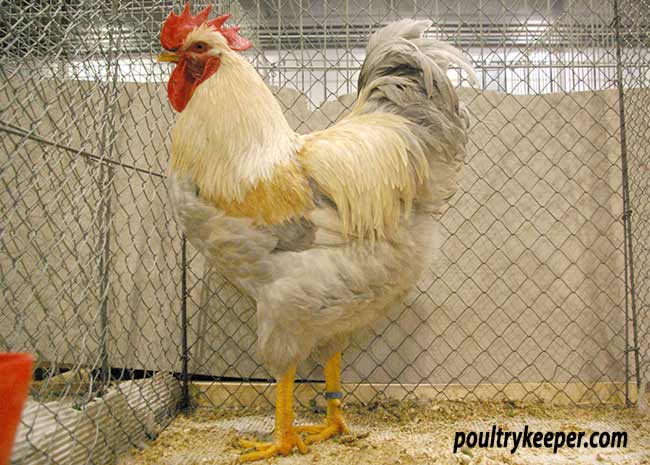

A Lavender Cochin Bantam male from Holland. Photo Courtesy of Ardjan Warnshuis

A Lavender Cochin Bantam male from Holland. Photo Courtesy of Ardjan Warnshuis

A Lavender Cochin Bantam female from Holland. Photo courtesy of Ardjan Warnshuis

The lavender gene’s effect on red pigment isn’t all bad; in varieties like Porcelain Barbu D’uccles (Belgian Bantam), it turns the ground color of females into a soft yellow shade, and the neck, saddle and shoulder of males a straw-yellow tone – making for an overall ‘pastel’ effect.

In Holland and Germany they have a color called ‘Isabel,’ which is created when the lavender gene is added to Partridge (or a similar variety such wild type or double-lacing).

The nomenclature does vary and not all agree what ‘Isabel’ should look like. And, on some parts of the Continent, what we know as Millefleur in the UK is actually referred to as ‘Porcelain.’

An Isable Barnevelder male at the Leipzig show held in Germany. Note how the lavender gene turns the red / orange pigment to straw / white.

An Isable Barnevelder male at the Leipzig show held in Germany. Note how the lavender gene turns the red / orange pigment to straw / white.