Anyone writing an article on the subject of poultry plumage has to begin with the 2 pigments that account for all the beautiful colours and patterns seen today. These pigments are black and red. They are best observed in the wild Red Jungle Fowl – the original form of chicken – and the one with a ‘wild type’ plumage.

When I write such articles, I really enjoy pointing out the areas of saturation of colour in the male and females, respectively. These are known as ‘sexually dimorphic’ regions and it’s easier to see how the black and red pigment is expressed in the male because they are region-specific. For example, black in breast, wing bar, thigh and tail, with red everywhere else. Females show some diffusion of the 2 pigments; the main areas being the back and thighs.

Changing it up

But it’s because we have the availability of genes to rearrange what nature intended, that we can have self-colours such as Buff or Black, or Gold-Laced which is a combination (a conflict) of the two pigments.

Bringing it back to a more basic level, I always explain in my articles that feathers begin white. ‘White pigment’ doesn’t exist, as many people think, more it is a case of a feather that is white has no pigment; and as we’ve discussed, ‘pigment’ comes in the form of either black or red.

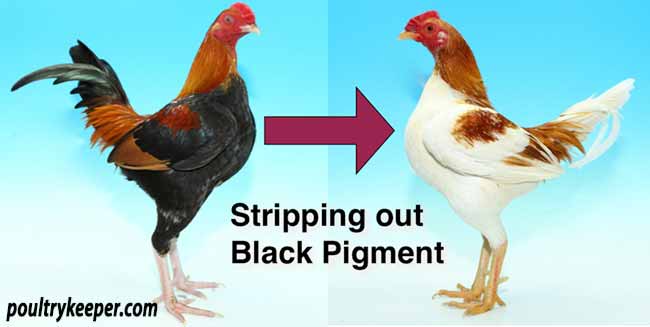

And one of my favourite colour forms is the Pile variety, which is most commonly seen in the Game breeds. This is possible by inhibiting (or ‘stripping’ if you like) the black pigment, only allowing the red to come to the feather, and obviously only ‘pigmentless’ feathers remain where the black should be, making for what I believe is a very pleasant effect.

Photos of Old English Game courtesy of Ian Wileman.

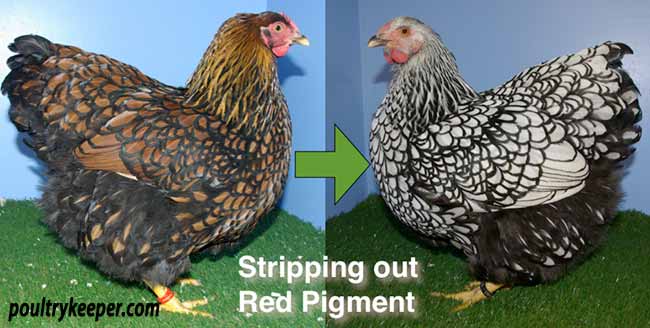

Another beautiful variety is possible by inhibiting the red pigment, and this, as you probably know, is known as Silver Duckwing in Game breeds. It is far more effective in the male, because the female has a salmon breast which cannot be altered by the same gene – it can only really effect her neck hackle.

And obviously, as you may imagine, by having the genes that strip both pigments out produces a white fowl. But this is just one of several ways of doing it.

Laced possibilities

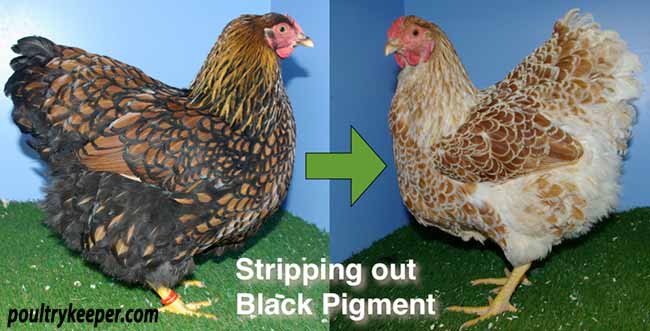

In Laced Wyandottes, 2 other varieties are possible by removing either the black or the red pigments. Take black away and you have a Buff-Laced Wyandotte; take red away and you have a Silver-Laced Wyandotte.

Now obviously there are Blue-Laced Wyandottes, which are produced by just diluting the black pigment, but we won’t cover that one today.

All white?

With the above in mind, it is quite easy to understand that whether the red or black pigment is inhibited that respective area is left ‘pigmentless’ and white. And while this is the way it appears, we need to remember that some effects are ‘dose-specific.’

When a Buff-Laced Wyandotte appears to have white lacing on a red ground colour, it is rarely questioned. Surely the same bird which also had its red pigment inhibited (by the Silver gene) would just appear as completely white? Well, yes, but in such cases the lack of red ground colour would highlight just how ‘dirty’ the actual lacing was.

I call this Ghost Lacing. With another dose of the gene that inhibits black pigment (Dominant white), the lacing would no doubt be cleaned up. Ironically, however, this also has the added effect of stripping out the red ground colour in Buff-Laced birds, meaning it will always be a challenge to get a clean white lacing on a red ground colour. But in saying that, without your attention being drawn to it, would you have noticed? I believe you can only truly appreciate how dirty ‘white lacing’ can be, when you see the example of Ghost-Laced. It’s the ground colour in question that highlights what’s really present.