As I alluded to in a recent article on the subject, there are many factors that got me interested in colour genetics of poultry. One of the main sources was the book ‘Bantams in Colour‘ first published in 1984 by Gold Cockerel books.

Little did I know at the time that both Michael and Victoria Roberts would one day become good friends of mine, or that Gold Cockerel would go on to publish 2 of my books!

Little did I know at the time that both Michael and Victoria Roberts would one day become good friends of mine, or that Gold Cockerel would go on to publish 2 of my books!

This book was my ‘Bible,’ as I referred to it. I was obsessed with all the different colours and patterns of poultry available. Before that, I had only known of hybrids and the odd pure breed such as the Rhode Island Red or Light Sussex.

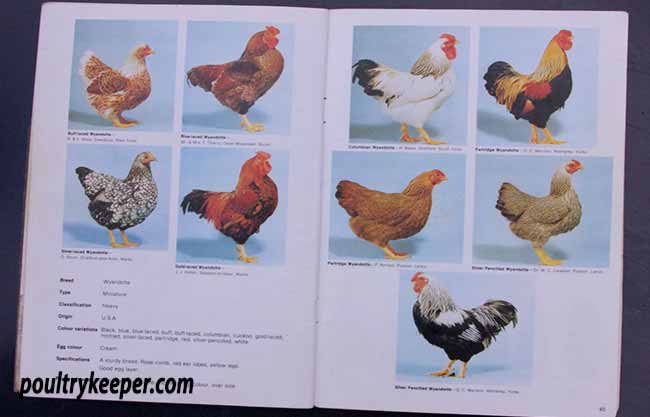

I was obsessed with certain pages in Bantams in Colour – particularly the Wyandottes and Hamburghs. The different plumage patterns were stunning, and I couldn’t help but question if, or how they were all interlinked.

The Wyandotte pages which got me contemplating the relationship between colour varieties

The Wyandotte pages which got me contemplating the relationship between colour varieties

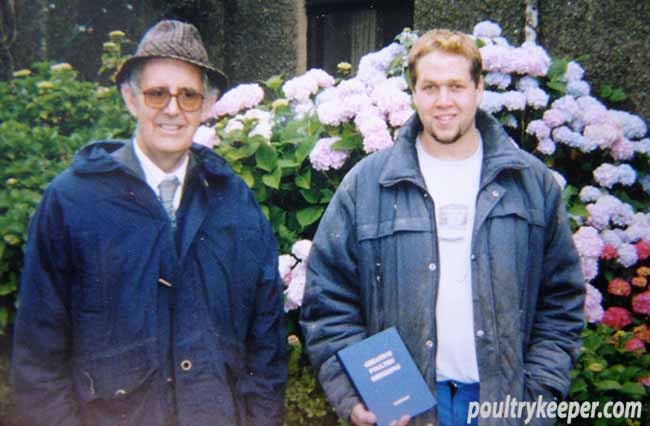

Dr Clive Carefoot

When Victoria Roberts told me there was a book on the market called ‘Creative Poultry Breeding’ by (now the late) Dr Clive Carefoot, I was really excited; I knew I had to get hold of a copy! Sadly, I soon learnt that the 500 print-run (first released in 1985) sold out very quickly, and that originals were worth a premium (assuming you could get someone to part with one).

I finally managed to gain access to an original copy through Cumbrian friend, Mike German, but it was only ‘on loan’ (a rather long one I must add).

With the late Dr Carefoot and his original book in 2003. Photo: Mike German

With the late Dr Carefoot and his original book in 2003. Photo: Mike German

I have to admit, I wasn’t awestruck initially by the publication, and the information that pertained to colour genetics looked like you needed a masters degree to understand it. I felt quite disappointed and that it didn’t really tell me much.

I did buy a photocopied manuscript direct from the author, but it was difficult to assimilate, especially when handling sheets of paper rather than a hardback book. Fortunately, Creative Poultry Breeding was reprinted a few years later in a limited run of 300 copies. I bought mine almost immediately and it was number 152!

I believe this book has now sold out, but publisher and specialist poultry bookseller, Veronica Mayhew will have more information on this. [Note. Veronica Mayhew has now retired – Ed]

After reading the reprinted Creative Poultry Breeding (in comfort and guilt-free), it dawned on me just how important a publication it was to the world of pure-breed poultry. Ok, you might not be able to glance at a page or two, then suddenly be able to come up with your own creations (which I think is what many of us want), but the amount of practical knowledge and hands-on experience in this book is unsurpassable.

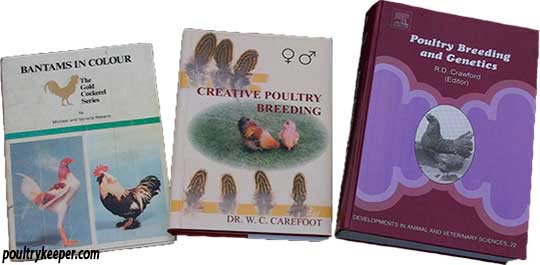

Much-treasured books: Bantams in Colour, Creative Poultry Breeding & Poultry Breeding and Genetics

Much-treasured books: Bantams in Colour, Creative Poultry Breeding & Poultry Breeding and Genetics

The author assumes a certain level of understanding – particularly when it comes to genes and their symbols, and this can be frustrating for the novice breeder. However, this is a publication that needs reading over and over; each time you will get something different from it. Whether you are creative or not, it’s the ultimate poultry breeder’s book.

The depth of knowledge of the subject matter, and thorough research into every aspect of it, is an accolade to which only Dr Clive Carefoot can lay claim. It is impossible to discuss poultry genetics without his name cropping up. He made many discoveries and observations in his years of breeding and laid the foundation for many others to begin to understand what it’s all about.

No fast-track (but do read on..)

There is no fast-track to understanding poultry genetics and this is something we all hate to hear. It’s like being told: ‘Work hard, get good grades and in years to come you’ll earn good money!’ It just sounds like: ‘Boooooooring!!’ – too much hard work and effort, and not attractive at all…

So, to counter this, my advice is to start small. Look at your breed and ask yourself what it is you want to know. I used to look at my Wyandottes, observing their rose combs and wonder what would happen if I crossed one to a single-combed breed. I used to ask the same question of yellow and white legs, and I learnt a lot from breeding a Buff Sussex male to Columbian Wyandotte females. The offspring all had rose combs and white legs. I thought: ‘Ah, so that’s what happens: the white legs appear to be dominant over yellow legs, and the rose comb appears to have the same effect over single combs – how interesting!’ I also learnt a lot about sex linkage from that cross – the males were all white with black hackles and the females were ginger; there were discernible differences in the day-old chick downs and I could immediately determine the sex of each chick (males yellow, females orange).

A purpose-made ‘sex-linked’ cross of a Partridge Wyandotte male over Light Sussex females

A purpose-made ‘sex-linked’ cross of a Partridge Wyandotte male over Light Sussex females

The offspring from the Partridge Wyandotte x Light Sussex. Note the sex-linked plumage, and inheritance of white legs from the Sussex and rose combs from the Wyandotte. All birds are Co/co+ (1 dose of Columbian inherited from the Light Sussex)

The offspring from the Partridge Wyandotte x Light Sussex. Note the sex-linked plumage, and inheritance of white legs from the Sussex and rose combs from the Wyandotte. All birds are Co/co+ (1 dose of Columbian inherited from the Light Sussex)

Although Dr Carefoot and his book taught me a degree in poultry genetics, it was other people who explained it better. They literally translated Creative Poultry Breeding (the genetics bits) into a language I could understand. I will always be grateful to Brian Reeder of the US and Clare Skelton of the UK for their longstanding help with this. They were obviously more capable than yours truly, of understanding and making sense of the information presented in that and other genetics publications. It may interest you to know that a book Clive recommended was called ‘Poultry Breeding and Genetics’ in which he featured, and is an accumulation of information edited by his American Scientist friend, R.D. Crawford. This book is still available today from Elsevier publishing (or Amazon).

Decoding the symbols

Even the minimum of gene symbols on paper can look like a ‘pile of dirty dishes’ – you just don’t want to face them!

The good news is they are only abbreviations AND look much more complex than the information they are supplying. In one of my Genetics Talks, I asked the audience to think of a statement and shout it out. One (witty) guy shouted: ‘I’m off down the pub for a pint of beer.’ I replied: ‘Great! Now we can all understand that.’ I proceeded by writing the same statement out on a flip-chart. ‘We can all understand that? Good.’ I then wrote it out in the following way: Io d+ P4p oB. I said: ‘Look – I’ve made a really simple statement look incredibly complex by abbreviating it – that’s all that’s happening with a lot of science terminology.

Another shout out came from the crowd: ‘So why do they make it look so ruddy complicated then – do they not want others to learn?’ My reply was that it was nothing to do with elitism or ‘holding information back,’ it’s just the way scientists write things out the quick way so that it fits in formulas and calculable equations – that’s all!

Let’s look at Columbian: its gene designation (symbol) is ‘Co.’ So if a breed has the Columbian gene (let’s say Light Sussex), it would be written as Co/Co. ‘Why the slash and why is it written twice?’ you may ask. Well, for any gene to breed true (aside from sex-linked ones), it needs to be present in 2 copies (what’s known as pure). This is simply to make sure the offspring are guaranteed to inherit a copy from each parent, and, as a result, themselves be in possession of 2 copies of the particular gene.

Where Clare Skelton came in…

I could understand the concept of Light Sussex being pure for Columbian and written as Co/Co. I could get that; it seemed fairly simple. But, I had a major problem with the way people used to write things like Co/co+ on genetics forums. ‘What the heck is that?’ I used to think, and it used to get me so frustrated.

In a late-night phone conversation with Clare, she explained that the ‘co+’ was not necessarily a gene (as I had thought), rather it was a ‘place’ to put Columbian. I was still a bit confused, but the penny was starting to drop. ‘So, you would never normally involve the ‘co+’ symbol if you weren’t discussing Columbian or the ‘impurity’ of it?’ I postulated. ‘That’s right’ she said, ‘Every breed of chicken that isn’t Columbian, has co+. The red jungle fowl would be co+/co+ because it is devoid of Columbian. Cross that bird to Light Sussex and the offspring would all be Co/co+ comprende?’ I think I did understand, and so can you. It needn’t be as difficult as you fear; the moral is: don’t be afraid of terminology!